Common Threads leads discussion on social determinants of health

Four Black physicians and public health experts share their perspectives on how communities can achieve health equity, particularly as communities grapple with COVID-19 pandemic

To help communities better understand the health disparities minority communities face, Common Threads hosted a virtual panel discussion attended by 140 participants on Aug. 10 entitled, “The Social Determinants of Health: An Examination and Discussion about Food Access, Nutrition and Obesity.”

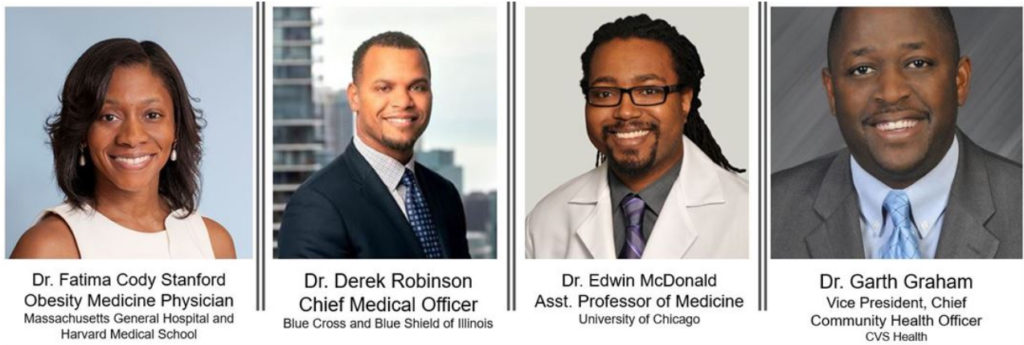

Moderated by Common Threads co-founder and CEO Linda Novick O’Keefe, panelists included Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine physician from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School; Dr. Derek Robinson, chief medical officer for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois; Dr. Edwin McDonald, a gastroenterologist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and Dr. Garth Graham, a cardiologist and vice president and chief community health officer from CVS Health.

The World Health Organization defines the social determinants of health as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” This can include factors that create physical environments, such as access to fresh food and green space and access to health services.

Social determinants of health can greatly influence health-related challenges that minority communities face. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a recent example, with LatinX and Black communities experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths, a phenomenon which experts are correlating with higher rates of obesity and overweight in these populations.

Dr. Graham, a cardiologist who previously led the Office of Minority Health for the Bush and Obama administrations, spoke to the need to consider the environment within each community. Unfortunately, many urban communities include a high density of liquor stores, fast food restaurants and Chinese restaurants, presenting an environmental barrier to wellness.

“The density and frequency and access point for these kinds of locations ultimately make unhealthy food the default decision,” Dr. Graham said.

Dr. Graham shared his view that the traditional public health model places too much emphasis on clinical care at a time when socioeconomic and environmental factors should be considered.

“Location trumps genes anytime because of how unhealthy we make locations nowadays,” Dr. Graham said, referencing his experience in treating heart disease in Black and brown communities.

Dr. McDonald reflected on the environment in which he grew up, attending church as a child living in the south side of Chicago. Each week he and his family would be asked to pray for members of his church who were battling diabetes, strokes or heart attacks. He remembers asking himself why so many people at his church faced these significant medical conditions and was soon realized it was his calling to enter the medical field and help reverse these trends.

“I believe in the power of prayer, but I also believe in the power of prevention,” Dr. McDonald said.

As a medical student, Dr. McDonald started volunteering for Project Brotherhood, a clinic focused on encouraging wellness for Black men on the south side of Chicago. The clinic has a unique approach: medical professionals wear street clothes as they gave consultations and treatment to visitors. Knowing that many Black men make frequent visits to the barber shop, barbers were placed adjacent to the clinic. Dr. McDonald, who is also a trained chef, began offering cooking demonstrations and classes for Project Brotherhood, later attending culinary school and offering cooking classes at his hospital.

Similarly, Dr. Stanford referenced some of her experience growing up in Atlanta. As a child, she and her sister associated church with how exciting the food would be, and she referenced the behaviors around wellness that are developed based on meals and activities that were planned after church. In some of her early research in the late 1990s, she and her colleagues developed church-based interventions, positioning Black professionals and actors such as Marla Gibbs as role models to educate the Black community on health and wellness.

“We need to go to people where they live and approach them from a place that’s culturally appropriate,” Dr. Stanford said.

The four practitioners agreed that the pandemic presented new challenges, but also new opportunities for professionals in the medical community to come together to solve longstanding public health concerns.

“This is a unique opportunity for us to stimulate and educate the masses around things they can do in their homes and in their neighborhoods that allows for social distancing and allows them to take better charge of their health,” Dr. Robinson said.

Dr. Stanford highlighted innovations that have surfaced as a result of COVID-19, such as providing prescriptions for WiFi service to help under-resourced communities gain access to health resources such as telemedicine and virtual wellness content.

“We need to get outside of our traditional swim lanes and pull some levers,” Dr. Robinson said. “We need a commitment across the board to make things happen.”

The full panel discussion is available on Common Threads’ Facebook and YouTube pages. The organization will offer additional panel discussions to bring light to current topics, including a session scheduled for Thursday, Sept. 24 entitled, “Beyond the Classroom: A federal, state, and local response to address student health and well-being during COVID-19.”